CHECK OUT THE GASTRECTOMY TREATMENTS- STOMACH REMOVAL EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW

CHECK OUT THE GASTRECTOMY TREATMENTS- STOMACH REMOVAL EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW

A gastrectomy is a medical procedure where all or part of the stomach is surgically removed.

When a gastrectomy is needed

A gastrectomy is often used to treat stomach cancer.

Less commonly, it’s used to treat:

life-threatening obesity

oesophageal cancer

stomach ulcers (peptic ulcers)

non-cancerous tumours

Gastrectomy is usually an effective treatment for cancer and obesity.

How a gastrectomy is performed

Our website has found some solutions how to know if gastrectomy is performed. There are 4 main types of gastrectomy, depending on which part of your stomach needs to be removed:

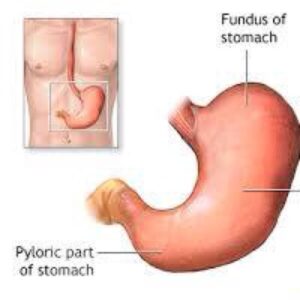

total gastrectomy – the whole stomach is removed

partial gastrectomy – the lower part of the stomach is removed

sleeve gastrectomy – the left side of the stomach is removed

oesophagogastrectomy – the top part of the stomach and part of the oesophagus (gullet), the tube connecting your throat to your stomach, is removed

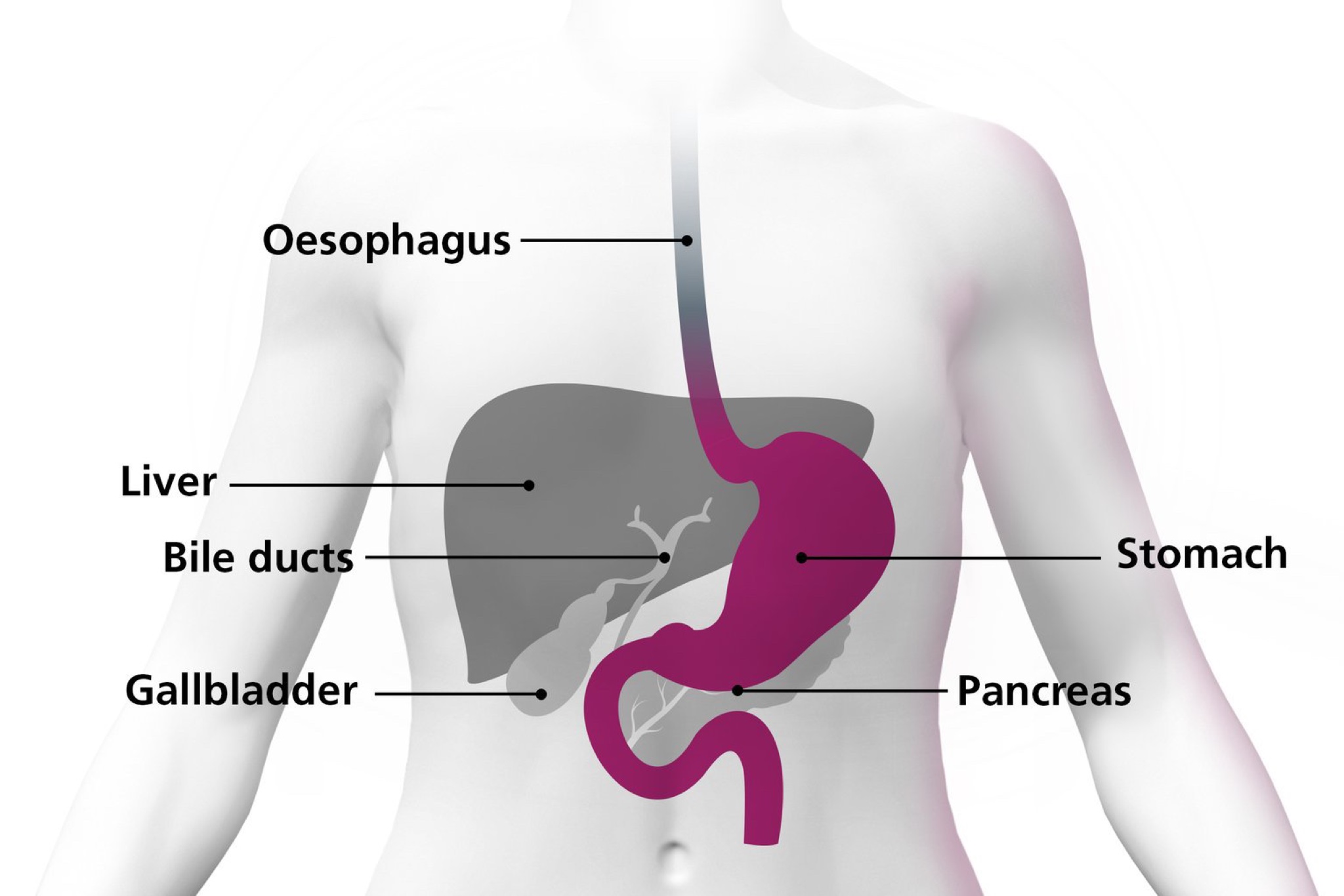

The stomach connects to the oesophagus (gullet) and the top of the small intestine

After surgery, you’ll still have a working digestive system although it will not function as well as it did before. If all or most of the stomach is removed, the gullet will be connected to the small intestine or the remaining section of the stomach.

check out BIOPSY REPORT WHAT IS BIOPSY REPORT AND EXAMPLE

Here are THE BEST 25 BIGGEST SOFTWARE COMPANIES IN THE US

most related news THE 9 BEST ACCOUNTING SOFTWARE FOR FREELANCER IN 2024

Check out ANTI INFLAMMATORY DIET A COMPLETE GUIDE TO EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW

All types of gastrectomy are carried out under general anaesthetic, so you’ll be asleep during the operation.

Techniques for gastrectomy

2 different techniques can be used to carry out a gastrectomy:

open gastrectomy – where a large cut is made in your stomach or chest

keyhole surgery (laparoscopic gastrectomy) – where several smaller cuts are made and surgical instruments are used

People who have keyhole surgery usually recover faster and have less pain after the procedure than those who have an open gastrectomy. You may also be able to leave hospital a little sooner.

Complication rates after keyhole surgery are similar to those for open gastrectomies.

Open gastrectomies are usually more effective in treating advanced stomach cancer than keyhole surgery is. This is because it’s usually easier to remove affected lymph nodes (small glands that are part of the immune system) during an open gastrectomy.

Before you decide which procedure to have, discuss the advantages and disadvantages with your surgeon.

Recovering after a gastrectomy

A gastrectomy is a major operation, so recovery can take a long time. You’ll usually stay in hospital for 1 or 2 weeks after the procedure, where you may receive nutrition directly into a vein until you can eat and drink again.

You’ll eventually be able to digest most foods and liquids. However, you may need to make changes to your diet, such as eating frequent small meals instead of 3 large meals a day. You may also need vitamin supplements to ensure you’re getting the correct nutrition.

Read more about recovering from a gastrectomy

A gastrectomy is a serious operation, and recovery can take a long time.

After the operation

After having a gastrectomy, you may be fitted with a nasogastric tube for about 48 hours. This is a thin tube that passes through your nose and down into your stomach or small intestine. It allows fluids produced by your stomach to be regularly removed, which will stop you feeling sick.

You’ll also have a flexible tube catheter placed in your bladder. This is to monitor your fluids, and to drain and collect urine while you recover.

Until you can eat and drink normally, nutrition will be given directly into a vein (intravenously) or through a tube inserted through your tummy into your bowel. Most people can begin eating a light diet about a week after a gastrectomy.

After the operation, you’ll need to take regular painkillers until you recover. Tell your treatment team if the painkillers you’re taking do not work – alternative painkillers are available.

You’ll probably be able to return home 1 to 2 weeks after having a gastrectomy.

Adjusting to a new diet

Whatever type of gastrectomy you have, you’ll need to make changes to your diet. It may be months before you can return to a more normal diet. A dietitian should be able to help you with this adjustment.

Food or drink you enjoyed before the operation may give you indigestion. You may find it helpful to keep a food diary to record the effects that certain types of food have on your digestion.

You’ll probably have to eat frequent small meals, rather than 3 large meals a day, for a fairly long time after having a gastrectomy. However, over time, your remaining stomach and small intestine will stretch and you’ll gradually be able to eat larger, less frequent meals.

The Oesophageal Patients Association (OPA) has a guide to life after stomach surgery containing lifestyle advice for people after they’ve had a gastrectomy

High-fibre foods

Avoid eating high-fibre foods immediately after having a gastrectomy, as they’ll make you feel uncomfortably full. High-fibre foods include:

wholegrain bread, rice and pasta

pulses – which are edible seeds that grow in a pod, such as peas, beans and lentils

oats – found in some breakfast cereals

You’ll gradually be able to increase the amount of fibre in your diet.

Vitamins and minerals

If you’ve had a partial gastrectomy, you may be able to get enough vitamins and minerals from your diet by eating foods that are high in nutrients – in particular, foods high in iron, calcium, and vitamins C and D. If you’ve had a total gastrectomy, you may be unable to get enough of these from your diet so may require supplements.

Read about vitamins and minerals for information on foods that are high in these nutrients.

Most people who have had a total gastrectomy, and some who have had a partial gastrectomy, need regular injections of vitamin B12 because this is difficult to absorb from food if your stomach has been removed.

After a gastrectomy, you’ll need regular blood tests to check you’re getting the right amounts of vitamins and minerals in your diet. Not enough nutrition can lead to problems such as anaemia.

9jahitsongs is one of the best entertainment Nigeria platform that broadcast the world latest news and entertainment news which deliver much entertainment gist worldwide Emmanuel zungwe is the author and the founder which has an over 5 years blog experience to provide you more information about THE GASTRECTOMY TREATMENTS- STOMACH REMOVAL EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW and entertainment quotes

Complications

As with any type of surgery, a gastrectomy carries a risk of complications, such as infection, bleeding and leaking from the area that’s been stitched together.

A gastrectomy may also lead to problems, such as anaemia or osteoporosis

DISCOVER MORE RELATED 9JAHITSONGS ARTICLES

HOW TO FIND A GREAT- TIPS FOR YOUR MUSIC PROMOTION

[DOWNLOAD MUSIC] MANXYHOTKING, ALBUM EP -BLOOD

[DOWNLOAD LATEST MUSIC] PRINCE G,O,K FT GBSON HUSTLE MP3

AYO MAFF DEALER LYRICS FT FIREBOY DML

check out and [DOWNLOAD MUSIC] MANXYHOTKING, ALBUM EP -BLOOD

Read more about-Complication

As with any type of surgery, a gastrectomy carries a risk of complications. Problems can also occur because of changes in the way you digest food.

Gastrectomy to treat cancer

Gastrectomies to treat stomach cancer carry a higher risk of complications because most people who have this type of surgery are elderly and often in poor health.

Complications can also occur after a gastrectomy to treat oesophageal cancer. The oesophagus, also called the gullet, is the tube connecting your throat to your stomach.

Possible complications of a gastrectomy include:

wound infection

leaking from a join made during surgery

stricture – where stomach acid leaks up into your oesophagus and causes scarring, leading to the oesophagus becoming narrow and constricted over time

chest infection

internal bleeding

blockage of the small intestine

An infection can usually be treated with antibiotics, but some other complications require further surgery. Before your operation, ask your surgeon to explain the possible risks and how likely they are.

Gastrectomy to treat obesity

Possible complications of a gastrectomy for obesity include:

nausea and vomiting – this usually gets better over time

internal bleeding

blood clots

leaking from where the stomach has been closed

acid reflux – where stomach acid leaks back up into the oesophagus

infection

It may be possible to treat some complications with medicine, but others may need further surgery. Before your operation, ask your surgeon to explain the possible risks and how likely they are to affect you.

Vitamin deficiency

One the stomach’s functions is to absorb vitamins – particularly vitamins B12, C and D – from the food you eat.

If your entire stomach has been removed, you may not get all the vitamins your body needs from your diet. This could lead to health conditions such as:

anaemia

increased vulnerability to infection

brittle bones (osteoporosis) and weakened muscles

Changing your diet may help to compensate for your stomach’s inability to absorb vitamins. However, you may need vitamin supplements even after changing your diet. The healthcare professionals treating you can advise on this.

Read about recovering from a gastrectomy for more information on diet and supplements.

Weight loss

Immediately after surgery, you may find that even eating a small meal makes you feel uncomfortably full. This could lead to weight loss.

Losing weight may be desirable if you’ve had a gastrectomy because you’re obese, but it can be a health risk if you’ve been treated for cancer.

Some people who have a gastrectomy regain weight once they have adjusted to the effects of surgery and have changed their diet. But if you continue to lose weight, see a dietitian. They can give you advice on how to gain weight without upsetting your digestive system.

Dumping syndrome

Dumping syndrome is a set of symptoms that can affect people after a gastrectomy. It’s caused when particularly sugary or starchy food moves suddenly into your small intestine.

Before a gastrectomy, your stomach digested most of the sugar and starch. However, after surgery, your small intestine has to draw in water from the rest of your body to help break down the food.

The amount of water that enters your small intestine can be as much as 1.5 litres (3 pints). Much of the extra water is taken from your blood, which means you experience a sudden fall in blood pressure. The drop in blood pressure can cause symptoms such as:

faintness

sweating

palpitations

a need to lie down

The extra water in your small intestine will cause symptoms such as:

bloating

rumbling noises

nausea

indigestion

diarrhoea

If you have dumping syndrome, resting for 20 to 45 minutes after eating a meal may help. To ease the symptoms of dumping syndrome:

eat slowly

avoid sugary foods – such as cakes, chocolate and sweets

slowly add more fibre to your diet

avoid soup and other liquid foods

eat smaller, more frequent meals

Seek advice from your hospital team or dietitian if you have symptoms of dumping syndrome. For most people, the symptoms improve over time.

Morning vomiting

After a partial gastrectomy, a small number of people may experience morning vomiting.

Vomiting occurs when bile – a fluid used by the digestive system to break down fats – and digestive juices build up in the first part of your small intestine (duodenum) overnight, before moving into what remains of your stomach.

Because of its reduced size, your stomach is likely to feel uncomfortably full, triggering a vomiting reflex to get rid of the excess fluids and bile.

Taking indigestion medicine, such as aluminium hydroxide, may help to reduce the symptoms of morning vomiting. See a GP if your symptoms are particularly bad.

Diarrhoea

During a gastrectomy, it’s sometimes necessary to cut a nerve called the vagus nerve, causing many people to experience bouts of diarrhoea. The vagus nerve helps to control the movement of food through your digestive system.

Speak to your doctor or nurse if you have diarrhoea, as treatments are available.

Most popular content BROW JOEL FT HYCE OGECHI

Check out KAESTYLE DEALER LYRICS FT OMAH LAY

more on SHYGIRL LYRICS MR USELESS

Check out more explanation in other way What Is a Gastrectomy?

Gastrectomy is surgery to remove all or part of the stomach. It changes the way you eat because your body must digest food differently. We can treat some small gastric tumors that have not spread with gastrectomy alone.

Gastrectomy is surgery to remove part or all of the stomach.

If only part of the stomach is removed, it is called partial gastrectomy

If the whole stomach is removed, it is called total gastrectomy

Description

The surgery is done while you are under general anesthesia (asleep and pain free). The surgeon makes a cut in the abdomen and removes all or part of the stomach, depending on the reason for the procedure.

Depending on what part of the stomach was removed, the intestine may need to be reconnected to the remaining stomach (partial gastrectomy) or to the esophagus (total gastrectomy).

Some surgeons can also do this surgery using a laparoscope. A laparoscope is a tiny camera that is inserted into your belly through a small cut. Video from the camera will appear on a monitor in the operating room. The surgeon views the monitor to do the surgery. When done this way, the surgery, which is called laparoscopy, is done with a few small surgical cuts. The advantages of this surgery are a faster recovery, less pain, and only a few small cuts.

Why the Procedure Is Performed

This surgery is used to treat stomach problems such as:

Bleeding

Inflammation

Cancer

Polyps (growth on the lining of the stomach)

Risks

Risks for anesthesia and surgery in general include:

Reactions to medicines or breathing problems

Bleeding, blood clots, or infection

Risks for this surgery include:

Leak from connection to the intestine which can cause infection or abscess

The connection to the intestine narrows, causing blockage

Before the Procedure

If you are a smoker, you should stop smoking several weeks before surgery and not start smoking again after surgery. Smoking slows recovery and increases the risk of problems. Tell your health care provider if you need help quitting.

Tell your surgeon or nurse:

If you are or might be pregnant

What medicines, vitamins, herbs, and other supplements you are taking, even ones you bought without a prescription

During the week before your surgery:

You may be asked to stop taking blood thinners. These include NSAIDs (aspirin, ibuprofen), vitamin E, warfarin (Coumadin), dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and clopidogrel (Plavix).

Ask your surgeon which drugs you should still take on the day of your surgery.

Prepare your home for when you go home after surgery. Set up your home to make your life easier and safer when you return.

On the day of your surgery:

Follow instructions about not eating and drinking.

Take the medicines your surgeon told you to take with a small sip of water.

Arrive at the hospital on time.

After the Procedure

You may stay in hospital for 6 to10 days.

After surgery, there may be a tube in your nose which will help keep your stomach empty. It is removed as soon as your bowels are working well.

Most people have pain from the surgery. You may receive a single medicine or a combination of medicines to control your pain. Tell your providers when you are having pain and if the medicines you are receiving control your pain.

How well you do after surgery depends on the reason for the surgery and your condition.

Ask your surgeon if there are any activities you shouldn’t do after you go home. It may take several weeks for you to recover fully. While you are taking narcotic pain medicines, you should not drive.

I HAVE BEEN DIAGNOSED WITH CANCER OF THE STOMACH. WHAT SHOULD I DO NEXT?

If you have being suffering much from cancer of stomach here are some of a explanation of what to do next to protect more of your health

Stomach cancer is diagnosed by endoscopy. The diagnosis of cancer is confirmed by laboratory examination of biopsies taken at endoscopy. You should urgently see a specialist once you have been diagnosed with stomach cancer. NHS hospitals in the UK have a system by which all patients with stomach cancer cared for by a specialist multi-disciplinary team (MDT). The entire MDT will discuss your case in their regular meetings and will remain involved throughout your treatment. Most private hospitals in the UK will not have a stomach cancer MDT. If you are having treatment in a private hospital, your case will be discussed by the MDT in the local NHS hospital. For example, if you see Mr Sarela at the Nuffield Hospital Leeds or the Spire Hospital Leeds, he will discuss your case in the MDT meeting at St James’s University Hospital.

IN THIS GUIDELINE WE WILL SHOW YOU WHAT ARE THE TYPES OF STOMACH CANCER?

The most common type of stomach cancer is called Adenocarcinoma. There are other types of stomach cancer called Neuroendocrine Carcinoma, Lymphoma and GIST (Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumour). These other types of cancer are rare as compared to adenocarcinoma. The treatment and prognosis are different for each of the four different types of stomach cancer.

HOW CAN I UNDERSTAND THE STAGE OF STOMACH ADENOCARCINOMA?

The stage of adenocarcinoma depends on three parts. First, how deep does the tumour penetrate into the stomach wall? This is called the ‘T’ stage of the cancer. The T stage can be T1, T2, T3 or T4. The numbering indicates the layer of the stomach wall that is involved by the cancer. A T1 cancer involves only the innermost layers, called the mucosa and sub-mucosa. If the tumour extends into the muscle layer, it is called T2. If it goes further into the outermost lining of the stomach, called the serosa, it is T3. The tumour is T4 if it goes into another organ, like the large bowel or pancreas that lie next to the stomach.

The second part of staging is about spread of the cancer to the lymph glands that lie next to the stomach. This is called the ‘N’ stage of the tumour. The stage is N0 is no lymph glands are involved by cancer. When there is spread to lymph glands, the stage may be N1, N2 or N3, depending on the number of glands that is involved.

The third part of staging is to find out if the cancer has spread outside the stomach and the nearby lymph glands. The three common places for spread of stomach cancer are the inner lining of the tummy wall (called the peritoneum), the liver and lymph glands far from stomach. The stage is M0 is there is no sign of spread. If the cancer has spread, the stage is M1.

These three parts together make up the TNM stage of cancer. For example, the tumour may be in the muscle layer of the stomach (T2) with no spread to lymph glands (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The TNM stage is expressed as T2N0M0. The cancer stage can be stated as 1, 2, 3 or 4 based on different combination of T and N and M. But, it is more useful to think and talk in terms of TNM for planning treatment.

Also, it is important to remember that staging depends on tests. Soon after the diagnosis, staging is done by scans and other tests. This is called radiological or clinical staging. If an operation is done at a later stage, then the tumour will be examined the pathology laboratory and a pathological stage will be given. The planning of treatment is done usually on the basis of the clinical stage because the pathological stage comes to light only later. The pathological stage can be different from the clinical stage because x-rays and scans cannot match the accuracy of pathology.

Please note that the staging system that is described here is for carcinomas of the stomach only. Other cancers, like GIST and lymphoma, have separate staging systems.

HERE ARE WHAT TESTS WILL I NEED TO HAVE TO FIND OUT THE STAGE OF THE CANCER OF MY STOMACH?

It is very important to find out the stage of stomach cancer because treatment depends on the stage. The first staging test is a CT scan. The purpose of the CT scan is to find out if the cancer has spread outside the stomach. Also, the CT scan can give valuable information about the location of the tumour in the stomach, the size of the tumour and the depth of penetration into the stomach wall.

CT scanning may give all the required information for some patients. Others may need additional tests. EUS (Endoscopic UltraSound) is a special type of endoscopy where an ultrasound scan is done from the inside of the oesophagus. This can give detailed information about the depth of the tumour and involvement of lymph glands alongside the stomach. Some patients may need to have a laparoscopy. The inside of the tummy is directly seen, and biopsies may be taken. Unlike cancer of the oesophagus, PET scan is not helpful generally for staging stomach cancer.

DO I NEED AN OPERATION FOR THE TREATMENT OF STOMACH ADENOCARCINOMA?

The decision about whether to do an operation for cancer of the stomach depends on two important factors. First, what is the stage of the cancer? And second, what is your general medical condition and fitness? Cancer of the stomach can be cured by an operation to remove the stomach and adjacent lymph glands. But, this is very major surgery and the decision should be made with great care. Broadly, there are three situations where an operation is not done:

1) An operation will not help if the cancer has spread already (stage M1). You will be referred to see an oncologist to discuss chemotherapy.

2) Even if the cancer is at a curable stage, a careful assessment has to be made of the risks of the operation for you, based on your individual fitness and medical problems. The fitness of your heart and lungs may need to checked by a cardiopulmonary exercise (CPX) test. You will be asked to pedal on a special exercise bicycle, with monitoring of your heart and lungs. If the risk of life-threatening complications seems too high, then non-surgical alternatives should be explored. Ultimately, the decision has to be tailor-made for you. If an operation is not felt to be suitable, you can see an oncologist to discuss chemotherapy.

3) An operation may not be needed if the cancer involves only the inner most layers of the wall of the stomach (stage T1). It may be possible to cut out the cancer by endoscopy (passing a flexible telescope-like camera down your mouth). This is called EMR (Endoscopic Mucosal Resection). The cut out cancer is examined in the pathology laboratory. An operation may be recommended after EMR if it appears that the cancer cannot be removed completely.

IS THERE ANY ALTERNATIVE TO AN OPERATION FOR THE CURE OF STOMACH ADENOCARCINOMA?

You should think very carefully about an operation if you have stomach adenocarcinoma at a curable stage. It is almost impossible to cure stomach cancer without an operation. The only exception is if the cancer is at a very early stage and it can be cut out by endoscopy (called Endoscopic Mucosal Resection or EMR). Chemotherapy or radiotherapy cannot cure stomach carcinoma.

IF I HAVE AN OPERATION, WILL I NEED CHEMOTHERAPY ALSO?

An operation alone may not be enough to cure stomach cancer. The tumour in the stomach and the surrounding lymph glands are taken out by the operation. But, there is risk that that cancer cells have spread already to other areas. The spread is microscopic and cannot be picked up by the staging tests or by inspection during the operation. These cells can grow after the operation and cause the cancer to come back (called recurrence of cancer). The risk of recurrence can be estimated by the pre-operative staging tests. For example, the risk is increased if the cancer has penetrated all the layers in the wall of the stomach, or if lymph nodes alongside the stomach are involved. Chemotherapy is often given before the operation to bring down the risk of recurrence. Many studies have shown that it is better to give chemotherapy upfront, before the operation rather than to wait until after the operation. You may be given chemotherapy both before and after the operation. Depending on your overall condition, sometimes it may be best to do the operation first. Radiotherapy is not used for the treatment of stomach carcinoma.

WHAT IS INVOLVED IN AN OPERATION FOR STOMACH ADENOCARCINOMA?

The operation is called a Gastrectomy, which means removal of the stomach. In a Total Gastrectomy, the entire stomach is removed. In a Sub-Total Gastrectomy about four-fifths of the lower stomach is removed. The uppermost part of stomach is preserved. The decision about whether to do total gastrectomy or sub-total gastrectomy depends mainly on the location of the tumour within the stomach and on the size of the tumour. We can make an estimate of the type of operation on the basis of endoscopy and scan findings. But, the final decision has to be made during the operation itself on the basis of the actual condition.

It is not enough to remove only the tumour because cancer cells can have spread in the wall of your stomach. Also, it is important to take out lymph glands that lie alongside the stomach because cancer cells may have spread to these glands. This is called lymphadenectomy. Removal of lymph glands that lie immediately next to stomach is called D1 lymphadenectomy. Removal the glands immediately next to the stomach plus the glands that lie along the blood vessels that supply the stomach is called D2 lymphadenectomy. For most patients, a curative operation will be a gastrectomy and a D2 lymphadenectomy. You may hear of it as D2 gastrectomy. After a total gastrectomy, the small bowel is joined to the oesophagus (gullet). After a sub-total gastrectomy the small bowel is joined to small portion of stomach that has been preserved.

Gastrectomy operations can be done by keyhole surgery (laparoscopy) or through a long cut on the tummy wall (open surgery).

WHAT IS THE RISK THAT ADENOCARCINOMA OF THE STOMACH CAN COME BACK AFTER AN OPERATION?

The risk that the cancer will come back (called recurrence of cancer) depends mainly on the final pathological stage of the cancer. The stomach and surrounding gland glands that are removed by surgery are examined in the detail in the pathology laboratory. The final stage takes various features of the cancer into account. How deep does the tumour go into the wall of stomach (T stage)? How many lymph glands are involved by cancer (N stage)? How close that the cancer go to the margin? Cancers at an early stage have better prognosis than advanced cancers. The prognosis is often stated as 5-year survival. This means the number of patients with that stage of cancer who will be alive after 5 years.

It is more difficult to estimate the prognosis before treatment has started. Staging tests are not always accurate. Sometimes, pathology may show that the tumour is more advanced than was shown by the pre-operative tests. Also, prognosis depends on your general fitness, response to chemotherapy and recovery from the operation. We can make estimates about prognosis based on your individual circumstances, but we cannot be certain.

WHAT IS A GIST?

GIST is a Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumour. A GIST is very different from the common type of stomach cancer called adenocarcinoma. GISTs arise from an entirely different cell-type than adenocarcinoma. GISTs vary greatly in aggressiveness. Some GISTs are benign whilst others are malignant. Like adenocarcinoma, the diagnosis of a GIST is made usually by endoscopy. But, because GISTs do not arise from the innermost layer of the stomach, biopsies that are taken at endoscopy usually look normal.

check out BIOPSY REPORT WHAT IS BIOPSY REPORT AND EXAMPLE

WHAT IS THE TREATMENT FOR A GIST?

Like any cancer, it is very important to do tests for staging before deciding upon treatment. The most important test is a CT scan. An operation to remove the GIST is needed if there is no sign of spread outside the stomach. The operation for GIST is different from an operation for the common type of stomach cancer called adenocarcinoma because GISTs do not spread into lymph vessels and lymph glands. So, it is usually sufficient to remove only the tumour rather than the whole stomach as is done for adenocarcinoma. Most operations for GIST can be done by keyhole surgery and long cuts on the tummy are not needed. If the GIST is large or if it has spread outside the stomach then a special type of medicine called Imanitib (Gleevac®) can be used to shrink the tumour before surgery. Also, some patients may benefit from Imanitib after the operation.

AT 9JAHITSONGS.COM YOU WILL GET ALL LATEST NEWS UPDATES AND CELEBRITIES NEWS TODAY

SHARE NEWS TO SPREAD LOVE

Check out SPYRO SHUT DOWN LYRICS FT PHYNO

2SLIZ ASSIGNMENT FT G I G GANGZ

PROMOTE YOUR MUSIC VIDEOS COMEDIES NEWS BIOGRAPHY DJ MIXTAPE AND MANY FOR TODAY WITH US

Do you find 9jahitsongs useful? Click here to give us five stars rating!

![[DOWNLOAD MUSIC]TERRI SNTANA-NACIDO DE NUEVO FT GIG GANGZ_ BORN AGAIN_ MP3](https://9jahitsongs.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/A50526EA-43C9-42A5-A8DD-8F554909604E.jpeg)

![[STREAM DOWNLOAD MUSIC ]JAH SPIDER-NHERERA_ MP3 / MORARI ALBUM](https://9jahitsongs.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/41C73EA6-8C57-49D6-B712-DF278056306B.jpeg)